How the Red Army built up and replenished its motor vehicle stock - crucial for logistics and fast moving operations. Lend-Lease was an important addition but far from being sole explanation of ability to maintain mobility. Remarkable piece by @HGWDavie https://t.co/5nBwYQe045 pic.twitter.com/iY4OCw5XjV

— Adam Tooze (@adam_tooze) January 7, 2021

How important were Lend-Lease trucks for the Red Army in WWII? This remarkable essay by @HGWDavie give us data on individual combat units e.g. 7th Guards Army. Answer: Domestic and trophy vehicles more important. https://t.co/5nBwYPWpcx pic.twitter.com/GxclCRyawC

— Adam Tooze (@adam_tooze) January 8, 2021

“This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in the JOURNAL OF SLAVIC MILITARY STUDIES Volume 31 Issue 4 on 15 October 2018, available online at doi.org/10.1080/13518046.2018.1521360. If you have access please click on this link to record your readership of this article."

Abstract

Motor vehicles have always been regarded as an indicator of modernity, technological advancement, and industrial progress, right from the time of the first motor car in 1885. The Soviet Union was no exception, and there is an extensive Soviet historiography of the development of motor transport and its use during the German-Soviet War. The aim of this article is to put the wartime military and economic use of Soviet vehicles into a wider context, highlighting how mechanization was not the only important variable in successful logistics. The case study here will be the role of transportation in the logistics of a Soviet combined arms army (общевойсковая армия) utilizing detailed primary source material from the pamyat-naroda.ru website.

The author would like to thank Mark Harrison of the University of Warwick for his assistance in the realization of this article.

A data appendix showing the principal tables used in this article can be found at https://www.hgwdavie.com/data-appendix/.

American architects and mechanics at Chebyalinsk Tractor Factory 1932

The spread of motorization in Europe

David Edgerton, in his book The Shock of the Old, makes the cogent point that our view of the advance of technology is skewed by a focus on invention and innovation, yet if that focus is redirected to ‘items actually in use’, this view shifts dramatically.1 He gives an example of the ‘mechanization’ of American agriculture around 1900, which surprisingly was based on horse power. The tractor only slowly replaced the horse as motive power on farms, with a peak in 1918 of 27 million horses on farms, followed by a steady decline with a midpoint around 1944 and a final low point in 1960.2 There were two fundamentals underlying this change, the high capital cost of the equipment and the need to provide it with its own infrastructure, which increased the capital cost still further. So American farmers had to make a large, initial investment in workshops and tools, fuel bowsers and spare tires, together with a first new tractor and then as horses died or retired, buy further tractors. In addition, the infrastructure had to service several farms in the same area, so mechanization tended to spread out from urban areas as part of wider social changes. By contrast, horses and mules had simple infrastructure that could be met by local supply and existing supply networks.

A similar pattern was seen in the spread of motor vehicles, which first appeared in 1885, as they needed infrastructure to make them usable. This meant hard, level roads; fuel and tires supplies from specialist manufacturers; workshops; spares; mechanics; and capital. So initially motors appeared in cities with high-intensity tasks such as buses and taxis to make the best use of the high capital expenditure. As the infrastructure improved, companies started to buy lorries for short haul journeys and to link the long-distance railway net- work with customers, although low cost, low-intensity usage, like delivering beer or farm-work, continued to remain with horse-drawn vehicles.3 Horse use remained dominant across the European rural economy, and mechanization took other forms such as electric milking parlors in Germany. In the most mechanized example, the United Kingdom, just 493,000 vehicles and 10,679 tractors had been produced by 1939, and it had a stock 3,157,000 vehicles and 52,000 tractors, (66 vehicles per 1,000 head) and 987,000 horses as of that year, while Germany by the same point had produced 376,769 vehicles and had a stock of 1,986,122 vehicles (25 vehicles per 1,000 head) and over 3 million horses.4

Albert Kahn - industrial architect to the Ford Motor Company and USSR

By 1938, the USSR had transformed itself from a backwards agricultural society and created a substantial heavy industrial sector; however, GDP per head was only 2,156 in 1990 US dollars per head of population5 compared to 6,430 in the USA and 4,685 for Germany, and the Soviet state lacked many other key industries such as electronics and optics. In 1928, the number of motor vehicles numbered only 16,400 (7,500 cars, 6,500 trucks, 1,100 buses, 1,300 specials,) plus 6,300 motor- cycles and 26,733 tractors,6 mainly imported lorries with a few thousand license- produced AMO F-15s from the Motor Car Moscow Factory, although many of these vehicles were non-runners or worn out. To create a motor industry from scratch, the latest technology and models were purchased from the United States to be produced under license. Working with the assistance of Albert Kahn Associates, a firm of American industrial architects who had just completed the Ford Motor Company’s massive Red River Rouge plant, in 1929 the Soviet government contracted to build a virtual copy in Nizhny Novgorod as the GAZ factory.7 Another US manufacturer, A. J. Brandt Co., helped expand the AMO factory into the ZIS factory to manufacture a licensed version of the Autocar Model CA as the ZIS-5. These two giant factories, together with three Kahndesigned tractors factories — The Kharkov Tractor Plant (KTZ), Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant (ChTZ), and Stalingrad Tractor Plant (STZ) making International Harvester and Caterpillar machines — provided the heart of the Soviet motor industry. In 1938 these factories produced 211,100 vehicles and 120,000 tractors, an output that is less than half the British and German totals. However, without the need to follow market forces, the Soviets were able to maximize the effectiveness of this new industry by focusing their efforts on lorries and tractors, making 182,400 lorries and 93,400 tractors8 that year compared to British totals of 113,946 and 10,6799 and German ones of 87,661 and 12,846.10 Yet, as so often in Soviet history, things did not go according to plan.

The collectivization of agriculture in 1928–1936 hit the wealthier, more efficient peasants the hardest — those with the highest horse ownership who slaughtered their horses and livestock before they were forced into new collective farms or deported. As a result of this and conditions on some collective farms, the horse population of 1927 of 30 million had fallen to 16.7 million by 1937, resulting in a fall in available horsepower on farms, despite the new tractors, which was not recovered until 1938. This was of concern to the Red Army, and the government was forced to set up state stud farms and take other measures to mitigate the effects.11 As shown in Graph 1, the Soviet stock of motor vehicles had reached 760,000 by 1939, yet production levels fell to 145,390 in 1940 due in part to interruptions in raw material supply, and the rise in stock also began to slow as the vehicles that had been produced in 1928 came to the end of their working lives.12

Motor vehicles statistics

Graph 1. Production and stock of Soviet national motor park

Motor vehicle statistics are as complex and open to interpretation as any other type, so care must be taken in assessing them. Levels of motorization have become a touchstone of operational mobility and seen as key to the success or failure of campaigns. Statistics conflate useful trucks with less useful cars or motorcycles and may include or ignore tractors and artillery prime movers and other combat vehicles. So it is important to understand the detail behind the headlines.

For instance, in Germany and the Second World War Vol IV,13 the authors claim that ‘427,284 trucks were received under Lend-Lease’ by the Soviet Union. By comparison, the Soviet Main Directorate of Motor Transport (GAVTU KA) figure is 312,600 light, cargo, prime movers, and special vehicles by 1 May 1945.14 The 427,284 figure appears in a table in Roads to Russia,15 which shows that 51,503 Jeeps and 362,288 trucks were dispatched from the USA, yet some 15,000 were destroyed and 5,000 diverted en route, and the figure covers the period right up to 1946.

The full picture is given in the 37 volumes of Report to Congress on Lend-Lease Operations, which shows that only some 400,000 vehicles had been dispatched to European Russia by 1 January 1945 (including motorcycles and tractors), with some 60,000 vehicles sent directly to the Far East to fight Japan, and the US total is further reduced by types of vehicles such as motorcycles and trailers that are counted separately in Soviet figures. The contribution of the British was relatively small, amounting to 4,343 lorries, 2,560 armored carriers, and 1,721 motorcycles.16 Once these losses, date, and classification differences are taken into account, the GAVTU KA figure is reasonably accurate, although it does not include several thousand 2½-tonne lorries that were diverted to the Main Artillery Directorate (GAU KA) for conversion to Katusha rocket launchers.17

The same book states that ‘approximately 600,000 motor vehicles and the same number of horses’ were used by Germany in Operation Barbarossa in June 1941. Yet the United States Strategic Bombing Survey Motor Vehicle Report18 states that the German Army had a total of 194,414 trucks and 145,085 passenger cars at the start of June 1941 plus 15,642 unarmored half tracks, which allows space for 100,000 Luftwaffe vehicles, 220,000 motorcycles, and a few thousand armored cars in the 600,000 total. In Soviet accounting methodology this would represent 365,000 motor vehicles with 15,000 tractors and 220,000 motorcycles. Readers need to be aware of the very different accounting methodologies employed by the major powers when comparing statistical information within this article with other sources.

Efficiency of transportation

For armies during the Second World War, mechanized transport was not always the most efficient form of transport. In the second edition of his book Supplying War, Martin van Creveld posed the question as to why a motor lorry with a potential range of 8,000 km often failed in practice to manage more than 800 km or 10% of its potential, while horse-drawn vehicles were able to realize a far greater proportion of theirs.19 Although van Creveld did not answer his own question, the answer lies with two inter-related factors, infrastructure and traffic.

An example of this is the use of ‘La voie sacrée’ during the battle of Verdun in 1916, when 4,300 vehicles supplied the French 2nd Army over a single 54 km road. These lorries required 16 labor battalions and thousands of tonnes of aggregate to keep the road surface repaired; a large group of loaders at either end to pack the lorries; and workshops, fuel bowsers, tire shops, and spares to keep the vehicles running and recover them when they broke down. Consequently, a lorry is only a single element in a complex system and is only as efficient as the infrastructure supporting it and the condition of the road on which it drives. The second factor is traffic, and there were control posts positioned along the road to regulate the flow of vehicles by ensuring that they kept to a common speed, that distances were maintained, and broken down ones were pushed off the road for later recovery. In this case there was no crossing traffic, so speed reductions due to crossroads, villages, bridges, and steep gradients were kept to a minimum and a constant flow maintained.

These effects were well known and codified in military manuals such as the British Field Service Pocket Book No.620 and in the German secret annex H.Dv.g.90 Versorgung des Feldheeres.21 These envisaged a lorry convoy traveling at 25 km/h, covering 15 km in the hour after reductions for traffic and a 10-minute stop for a rest and minor repairs. Vehicles maintained 80 meter spacing or 12 vehicles to a kilometer and 180 vehicles passing a point in one hour. The length of the working day was 14 hours, and it was assumed that the convoys could travel up to 200 km a day or 100 km in a round trip. The length of the vehicle column meant that 2,400 vehicles could travel down the road in one day with several hours allowed for road repairs. For 1-tonne vehicles this equated to 480,000 tonne km using the formula:

‘H.Dv.g. 90 Versorgung des Feldheeres (V.d.F.) Teil II’

Where L = daily amount carried in ‘tonne km’, 14 = number of working hours, X = number of journeys per day, 225 = a constant of average speed (15 km/h by 0.5 to account for return journeys, Y = number of 30t motor columns, Z = the state of the road (2.5 for highways, 1.6 main roads, 1 hard roads, 0.7 field roads or gradients). Any given road had a maximum capacity of the number of vehicles that it could handle in one day, and the only way to increase its capacity was to use vehicles with larger loads. Also for a given size of transport fleet, every extra day of journey would reduce the amount hauled to the destination. A 30- tonne motor column could haul its load in a 100 km round trip; however, it could only deliver 5 tonnes a day at 600 km. The number of columns would have to be increased sixfold in order to keep deliveries at 30 tonnes a day, and this is what Fernand Braudel called the ‘tyranny of distance’.22

This had implications for the supply of armies and restricted their supply routes to good roads, as only these could facilitate the necessary speed and capacity. Only in the last 25 km from divisional supply points to the frontline units did cross-country vehicles or indeed horse-drawn vehicles convey any advantage from their ability to cover rough ground. A Studebaker-type lorry23 on the road could carry 4-tonnes24 and traveled at 70 km/h unloaded and 59 km/h fully loaded with a fuel consumption of 3.2 km/l; however, crossWhere L = daily amount carried in ‘tonne km’, 14 = number of working hours, X = number of journeys per day, 225 = a constant of average speed (15 km/h by 0.5 to account for return journeys, Y = number of 30t motor columns, Z = the state of the road (2.5 for highways, 1.6 main roads, 1 hard roads, 0.7 field roads or gradients). Any given road had a maximum capacity of the number of vehicles that it could handle in one day, and the only way to increase its capacity was to use vehicles with larger loads. Also for a given size of transport fleet, every extra day of journey would reduce the amount hauled to the destination. A 30- tonne motor column could haul its load in a 100 km round trip; however, it could only deliver 5 tonnes a day at 600 km. The number of columns would have to be increased sixfold in order to keep deliveries at 30 tonnes a day, and this is what Fernand Braudel called the ‘tyranny of distance’.22 This had implications for the supply of armies and restricted their supply routes to good roads, as only these could facilitate the necessary speed and capacity. Only in the last 25 km from divisional supply points to the frontline units did cross-country vehicles or indeed horse-drawn vehicles convey any advantage from their ability to cover rough ground. A Studebaker-type lorry23 on the road could carry 4-tonnes24 and traveled at 70 km/h unloaded and 59 km/h fully loaded with a fuel consumption of 3.2 km/l; however, cross-country its maximum speed was only 25 km/h, fuel consumption rose to 1.2 km/l, and load was limited to 2½-tonnes. It is clear from Red Army records that the majority of such cross-country vehicles were regarded as prime movers for artillery and anti-tank guns and that the rear used the two-wheel drive GAZ-AA and Ford-6 1-tonne lorries as its mainstay.25

The same restrictions applied to horse-drawn vehicles, with the important exception that wagons covered 32 km in the horse’s eight-hour working day and retained their higher efficiency because all the wagons naturally moved at their optimum cruising speed of four km/h. Unlike motor vehicles, which had an engine with a large reserve of power, horse teams drew close to their maximum weight on the flat and had to add additional horses to overcome steep gradients. Yet the robust construction of wagons and their relatively light weight meant that they retained most of their performance cross-country and could often cross linear obstacles that defeated motor vehicles lacking sapper support.

Transportation in European armies

Female fighter pilots push a truck, Crimea 1944

In 1939, the majority of European armies were established on a consistent pattern of a mass infantry arm supported by heavy artillery, with a small proportion, around 15% of units, containing tanks and being fully motorized. While this represented an improvement on the armies of 1918, there were many similarities as the mass infantry divisions retained their horse-drawn field guns, unit transport, and divisional transport with only specific subunits such as reconnaissance and anti-tank gun battalions being motorized and lorry columns providing the link between the divisional supply point and the army depot.

The German Infanterie-Division 1.Welle of 1939 was both typical and illustrative of the pressures of motorization on armies, as in 1939 it contained 17,734 men, 1,743 saddle, and 3,099 draft horses with 950 carts/wagons, 500 bicycles, 394 cars, and 615 lorries, 67 trailers, and 326 solo and 201 side-car motorcycles.26 The key supply link was provided by eight small motor columns (30t), one fuel column (25 cubic meters cbm), and three each of two types of artillery columns (36t and 28t). Following the Polish campaign, the combination of losses and the insufficient supply of new vehicles to the German Army (Heer) prompted the Chief of the General Staff, Gen. Franz Halder, to write in his diary27 that he was considering de-motorizing the Heer due to shrinking vehicle stocks.28 To find vehicles for the French campaign, infantry division artillery regiments lost their artillery columns. The defeat of France resulted in a one-off addition of 200,000 vehicles to the Heer from captured French and British stocks, although the need to expand the original six to 10 and later 21 Panzer divisions required that the infantry divisions exchange more motor vehicles for horse-drawn ones. Of 153 infantry divisions available to the Heer in June 1941, no less than 130 had an establishment of three small motor columns (30t), three horsedrawn columns (30t), one fuel column (25cbm), and three light columns (15t), while the remainder had even fewer motors.29 What this meant in practice was that the infantry division in 1939 could support itself for about 75 km from the Army depots, but by 1941 this distance had halved, so just when the Heer needed logistical reach it had to sacrifice it to gain an enlarged Panzer arm.30

Tempo of horse-drawn operations

The work of transport historians such as Dorian Gerhold demonstrates that at its peak in the 1820s horse-drawn transport was capable of moving a 2- tonne wagon with a 6-tonne load (drawn by eight draft horses each pulling 1,000 kg) along a series of ‘stages’ or etappe up to 95 km a day or the lighter vans with trotting horses up to 240 km a day. It was found that improving the road surface only had a minimal effect on speed, where the real enemy of horse-drawn transport was steep gradients.31 For military purposes, Perjes has shown that Early Modern armies adapted their campaigning season to the agricultural year, waiting until the grass started growing in May before taking to the field and feeding their horses rich spring grass until harvest time in late July before switching to hay and oats drawn from the local area until the end of the campaigning season in November.32 Campaigning proceeded slowly, with armies marching from tented camp to camp spending approximately 1.5 days a week on the road, covering 32 km a week and the rest in camps or engaged in sieges, with supplies carried by wagon trains from depots based in river towns.33 Even active generals such as Frederick the Great only managed to march for 2.5 days, covering 64 km a week.

The Russian author Egor F. Kankrin described how this system changed around 1800 with an increase in the tempo to four to five days marching covering 115 km a week, with the abandoning both of tented camps and, to a large extent, supply trains. This was brought about thanks to the invention of the greatcoat allowing tents to be abandoned, replacing bread with biscuits, the splitting of armies into corps of 30,000 men, and a rise in agricultural efficiency and population density. Using his experience as a Russian army intendant, Kankrin established that a corps could use the local administration and agricultural infrastructure to collect supplies if the population exceeded 25 head per km sq, or a mix of this and supply from depots could be sustained at 18 head per km sq. This allowed transport to be reduced to a minimum of 12½ wagons per thousand men.34

For this reason, when railways arrived in the 1840s, they were largely ignored by the European military, and it was only during the American Civil War, when Union armies were campaigning in the southern states with a population of 4.6 head per km2, that they had to resort to railways to bring forward supplies, by tapping into the agricultural markets that were forming to feed northern cities. Yet this reversion to railway supply caused a crisis in mobility as Union armies increased the weight of supplies required. This was due to higher standards of living for soldiers, expanded medical services, larger cavalry forces, and bigger artillery trains, all supported by a limited amount of horse-drawn transportation, reaching as many as 70 wagons per thousand men. This might be termed the ‘tyranny of weight’ and the ‘tyranny of demand’. However, it was mitigated by Quartermaster Meiggs and General Sherman imposing strict limits on both demand and baggage and tailoring combat forces to their missions, which restored the tempo of operations and mobility. Sherman went one stage further, using railways and supply convoys during the Atlanta campaign and then further reducing his army’s combat power and weight so that he could live by foraging and requisition on the ‘March to the Sea’, so returning to a Napoleonic tempo of operations covering 800 km in 29 days at 24 km per day, albeit with a wagon standard of 40 per thousand.35

After 1900, armies found themselves under pressure again from the twin tyrannies of weight, as new equipment such as machine guns, telephones, and ambulances was added to their establishment, and demand — for the ammunition consumed by quick-fire artillery exceeded the quantity that could be carried on unit transport.36 A German infantry battalion — which in 1870 had 20 horses, four wagons, and four pack-horses — had grown by 1914 to 58 horses and 19 wagons and by 1939 to 135 draft and 37 riding horses, 68 wagons/carts, and seven motorcycles. Heavier equipment such as the replacement of the 7.7 cm FK16 field gun with the 10.5 cm leFH18 howitzer raised the load pulled by artillery teams to over 4 tonnes.37 When coupled with the increasing size of armies, it had the effect of tying armies to railway lines and reducing the tempo of operations, moving away from Kankrin’s model of a free moving army. The German army in August 1914 marched 400 km in 20 days or just 18 km a day, yet Germany’s lauded Michael offensive in March 1918 covered only 70 km in 15 days or an average of 5 km a day. Distance was not the problem, as all of these marches were well within the capability of largely horse-drawn transport, but the combination of weight, too much cavalry, heavy artillery and equipment, and demand, mainly in artillery ammunition consumption.

Combined horse-drawn and motor operations

The Heer’s reliance on a small motorized Panzer force and a larger, horse-drawn infantry force during the early years of the Second World War and the limitations this imposed in terms of range of operation have been exposed in the academic literature for some time — for example, in 1971 by Larry H. Addington.38 The key point from these studies is highlighting the short distance that German armies were able to operate away from railway lines and hence during the Soviet-German War, the great efforts made by the railway engineers (Eisenbahnpionieretruppen) to open railway services within a week of the advance. This focus delayed the establishment of high-capacity railway lines linking the depots in Poland with the supply districts (Versorgungsbezirke), which in turn reduced the ability of the armies to penetrate deeper into Soviet territory and caused later logistical shortages.39 The tempo of operations is illustrated by the example of the IX Armeekorps of Army Group Center, which left Minsk on 9 July 1941 having completed the destruction of the frontier pockets and marched through Borisov, Krupki, Gorki, and Krasnyi to Pochinok by 25 July, where it was halted by Soviet counter-attacks around Smolensk, with the 400 km march being covered at an average of 28 km a day.40

By contrast, the Red Army had a clear understanding of operating horse-drawn armies in areas of low population density, gained from Tsarist colonial expeditions, the Russo-Japanese War, Great War, and Polish-Soviet War, demonstrating in the latter an ability to move armies at rates of 30 km per day over a period of several weeks.41 This experience and understanding survived the doctrinal turmoil of the Purges and was incorporated in the re-emerging ‘Deep Operations’ doctrine, which assigned different roles to the various parts of the army that reflected their transport capability. The combined-arms armies provided the combat power to penetrate the enemy defensive line, encircle and destroy enemy local units, combat the inevitable armored counter-attack, and then exploit into the depths of the enemy territory, reducing enemy strong-points as they advanced. They carried the main burden of combat, while the tank army would aim to transit the breach in the enemy line, without becoming engaged, and then drive off into the operational depth with the aim of unhinging the next line of enemy defense. The tank army would aim to engage in combat deep in the operational depths, paving the way for the rifle divisions when they arrived to hold the objective. This was in direct contrast with German methodology used in the first encirclement battles of June 1941, where the Panzer divisions created the penetration in the enemy line, encircled the defenders, and then had to wait for the horse-drawn infantry divisions to march up to reduce the pocket. This close interdependence between German units of differing mobility in achieving the same mission caused problems that led to changes in later operations yet was never totally resolved. The Soviet tank armies were fully motorized, which enabled them to move quickly up to 30 km a day, whereas the horse-drawn combined-arms armies moved at 12–15 km a day while the railway troops restored the railways at rates ranging from 5–12 km a day. This meant that the combined-arms armies outran the railways after 15 days, when the rifle divisions had moved 225 km and the railways 75 km, separated by 150 km. These were the rates of advance used for planning in June 1944; however, they were exceeded during the Vistula-Oder Operation in January 1945, with tank armies covering between 45 and 70 km a day and combined-arms armies 30 km a day.42 These separate, albeit related, functions assigned to the two army types ensured that differing rates of advance did not cause the same operational problems that beset the Heer.

Wartime military and civil fleets

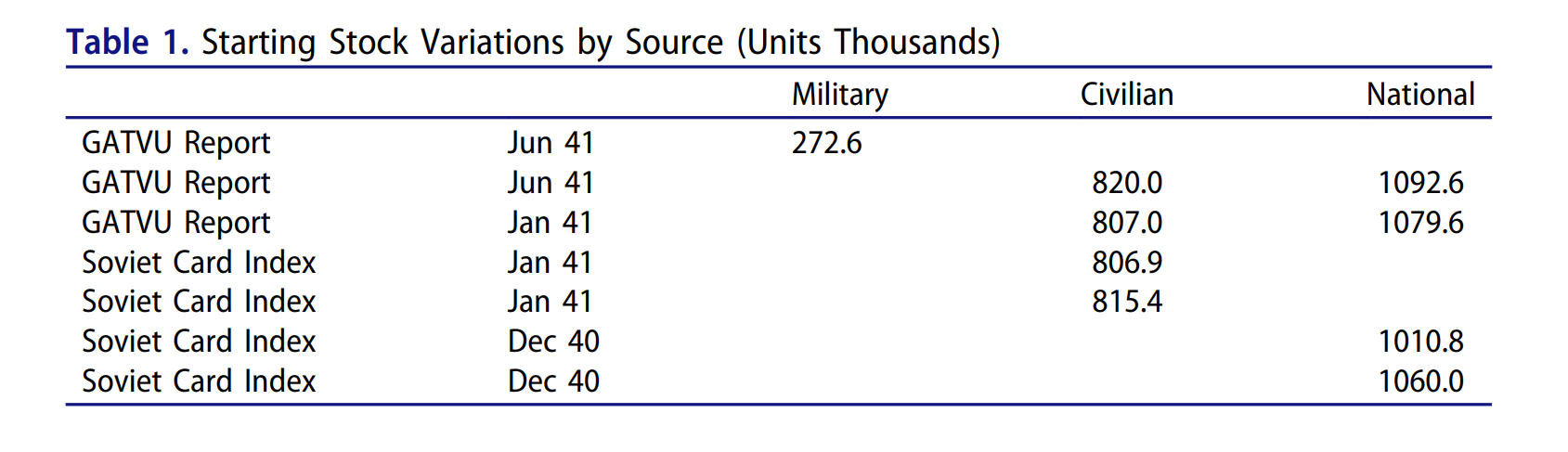

There are two principal sources that can be used to provide an overview of the wartime Soviet motor fleet, firstly a GAVTU KA report written in September 1945 gives considerable detail on the military fleet and includes a small section on the civil sector.43 This can be combined with statistics from the Card File of Motor Transport produced by the State Planning Committee (GOSPLAN) to build up a picture of the national motor park.44 However, the material balances derived from this data, given in Tables 1–4, do not have the same level of accuracy, with the military one being the better and the civil and national pictures being less accurate, as they rely to some degree on a level of assumptions and calculation.

There are a number of discrepancies within the GAVTU report and between it and the Card File and other supporting sources. The most obvious of these is the range of starting stocks in 1941, as detailed in Table 1 — for instance, GAVTU claims 272,600 military vehicles and 820,000 civilian vehicles, a total of 1,092,600 in the national park. Yet GOSPLAN gives a stock figure of 1,010,000 at year end 1940, with an annual scrappage rate of 53,200 for 1940 and production of 78,100 vehicles up to June 1941, which makes the GAVTU figure look too high.45 Nonetheless it is possible to observe broad themes within this data set so long as these restrictions are borne in mind.

By January 1941 the civilian fleet had grown to 806,900 vehicles (106,900 passenger cars, 8,200 pickups, 655,700 cargo, 28,900 special purpose, 15,200 buses) and 61,700 trailers, 38,600 motorcycles, and 556,400 tractors. Of these, 249,000 were in the rural economy, 21,800 collective economy, 180,400 industry, 55,100 transport, 8,800 telephones, and 51,100 trade.46 The balance of the 1,010,000 vehicles in the national park provided the Red Army with around 203,000 vehicles, which left it in a parlous state, as the wartime complement called for 755,878 vehicles, 94,584 tractors, 73,047 motorcycles, and 97,598 trailers. A further 200,000 vehicles were to come from the civil economy upon mobilization, but this would still leave the Red Army over a quarter of a million vehicles short, or 62% of establishment and current levels of production would not close the gap for some years. In the absence of motor transport, units would rely on horse-drawn transport, and the Red Army had 168,300 two-horse wagons, 51,500 one-horse wagons, 16,500 ambulances, 3,500 pharmacy carts, 8,600 infantry/artillery, and 20,000 cavalry field kitchens available, a total of 268,600, although the establishment was 321,800.

From this starting point, the GAVTU KA report allows the creation of a material balance for the Red Army motor fleet during the course of the rest of the war Table 2, and it is possible to build up a picture of the new vehicles joining from home production, imports, transfers of vehicles to and from the civil economy, and trophy vehicles. The picture that emerges is of a steady rise in numbers despite large losses in 1941 and heavy losses in 1942–43.

Although the GAVTU KA report only gives outline figures for the civil economy, a comparable material balance can be built up from the data in the Card File of Motor Transport,47 and an attempt can be made to chart the inputs and outputs into the civilian fleet in Table 3.

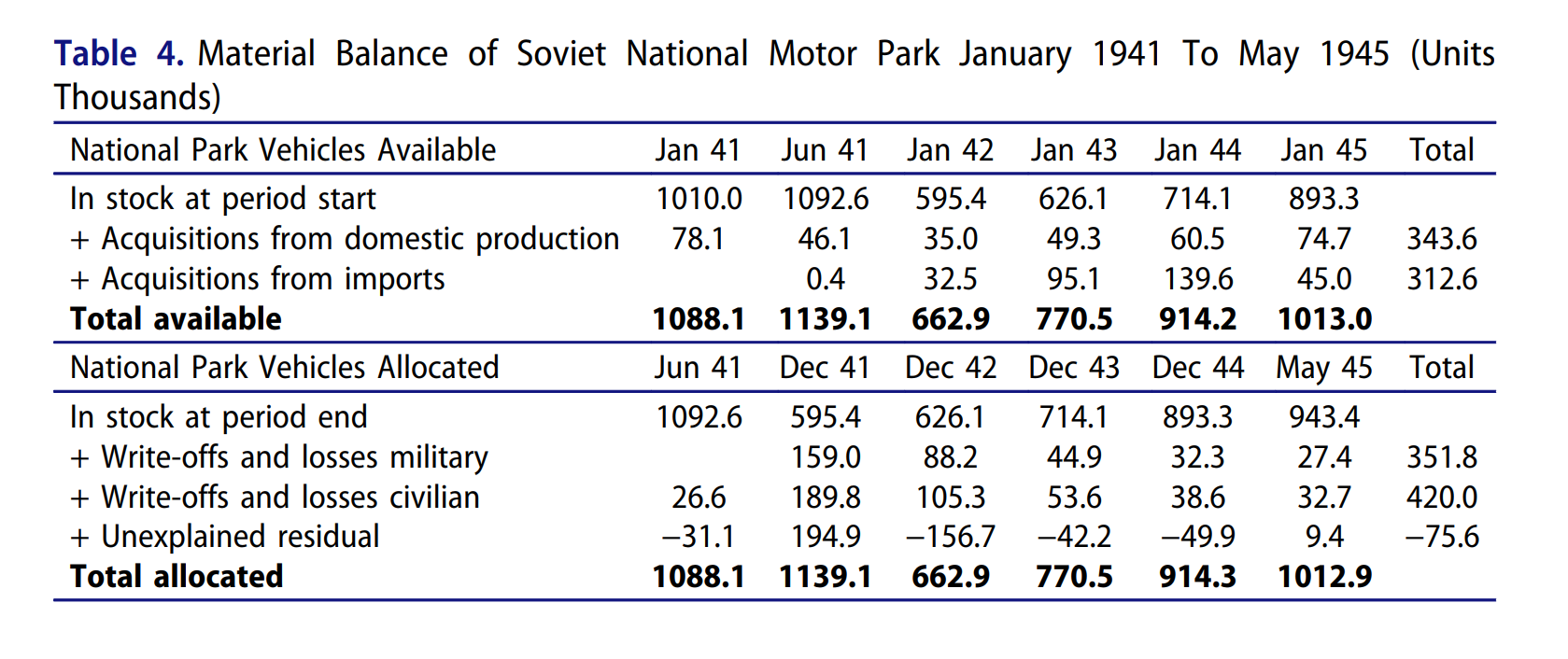

Given these caveats, the military and civil data from both sources can be combined to give an overall picture of the Soviet motor fleet during the war as shown in Table 4.

The picture that emerges from these tables is subtly different from the picture often associated with the Soviet military, as the national fleet of one million vehicles suffered a huge shock in 1941 that cut it by over a third, and although it slowly began to recover its strength from 1942 onward, nonetheless it continued to suffer heavy losses, so that by the end of the war the fleet was still smaller than at the start. Losses were enormous: up to 771,800 vehicles (351,800 for the army and 420,000 for the civil economy) in effect wiping out the entire fleet that had been built up between 1928 and 1939, while wartime production between 22 June 1941 and 9 May 1945 was 212,200 vehicles and imports delivered 312,600 vehicles, a total of 524,800.

This gave a net loss of 145,400 vehicles over the wartime period, and given this, the only way the army could grow its motor fleet was at the expense of the civil fleet, both in terms of transfer of vehicles and taking the bulk of new production and imports so that the civil fleet fell from 820,000 vehicles in June 1941 to 292,000 by May 1945. The tractor fleet suffered a similar fate. With the main burden of this civilian vehicle conscription falling on Soviet agriculture, there were serious consequences for its efficiency in gathering in the harvest from the recovered territories in 1944–45 and post-war.

Levels of transportation obtained from the military fleet

Vehicles were ubiquitous and were found at all levels of military administration, in the field army, in the military districts, and with the STAVKA reserve; moreover, the Red Army had a large fleet of horse-drawn vehicles deployed in its rifle divisions.48 Table 5 shows the evolving balance of transportation during the war, within the overall Red Army and specifically the transportation deployed to the field army at the front. During the first period of the war,49 Table 5 the original peacetime army was destroyed, and the newly raised armies halted the German advance outside Moscow in December 1941. At that point the army numbered just under 9 million men (45% in the field army at the front) and possessed 28 men per vehicle, 245 men per tractor, and 6.9 men per horse (the field army had 20 men per vehicle, 233 men per tractor, and 6.6 men per horse.) At the end of the first period, the Red Army had grown by a million and a half personnel (62% were in the field army), yet the vehicle fleet had grown in line with this and remained at 28 men per vehicle, although shortages of horses and tractors had caused their ratios to fall to respectively to 290 and 10 men per item. However, the high concentration of men at the front caused a transport shortage in the field army at a level of 25 men per vehicle, 312 men per tractor, and 8.45 men per horse.

The situation had not eased by July 1943, as the Red Army grew by 1.3 million personnel and the transport situation worsened further. The increasing number of vehicles meant that the Red Army managed to hold the numbers for vehicles and tractors at their former levels, yet the overall fall in the number of horses due to heavy casualties in the winter pushed the levels up to 12.8 men per horse for the Red Army and 11.4 for the field army. The second period of the war proved to be the lowest ebb for Red Army transport and compared unfavorably with British forces, which were half its size but operated 2.5 times the number of vehicles, having at this stage of the war more vehicles than the Red Army would have in 1945. Eyewitness accounts such as that of Alexander Werth noted the large number of horse-drawn wagons in the rear of the front and failed to see any imported vehicles during the Stalingrad Operation and first observed them during the Kursk Operation. By January 1943, the Don Front was operating 9,420 vehicles during Operation Ring but only deployed 3,600 vehicles in motor units at the front level to support a force of 284,000 men in the depths of winter.50 The transport levels improved from mid-summer 1943, as the Red Army ceased expanding and established a stable level of manpower for the rest of the war. This allowed the steadily increasing number of vehicles to ease the transport situation, and the recapture of the Ukraine and its horse stocks enabled a strong recovery of horse numbers back to their 1942 levels.

At the start of the third period, the Red Army had 24 men per vehicle, 236 men per tractor, and 12 men per horse, with around 60% of its manpower deployed in the field army, which had 22 men per vehicle, 208 per tractor, and 10 per horse. The steady growth in all these categories throughout 1944 finally returned the field army by January 1945 to the transport levels it had last seen in December 1941, with 18 men per vehicle, 201 per tractor, and 8.5 per horse. In January 1945 the Red Army as a whole had improved its vehicle position, having 21 men per vehicle compared to 28 in 1941, but this was offset by a higher proportion of personnel serving with the field army — 60% compared to 45%. Some researchers have claimed that the increasing number of Lend-Lease vehicles improved the transport capabilities of the Red Army and allowed it a higher tempo of advance during the summer of 1944. While the overall number of vehicles did rise between 1942 and 1945, this does not take into account the increase in size of the Red Army between 1941 and 1943; it added 3 million personnel to the total and more importantly, the increasingly high proportion of personnel assigned to the field army. This is demonstrated by the shortfall in vehicle establishment numbers suffered by even the most favored of units, the tank and mechanized corps, which were regularly 25%–30% below establishment in vehicles.51

Nor was the level of motor vehicle transport deployed by the Red Army close to the level used by the British, who by June 1945 had 7.7 men per vehicle — with fewer troops they used more vehicles, as the field armies in France and Italy numbered a maximum of 2.4 million. The Red Army was effectively less than half as motorized as the British armed forces, and its shortfall in transport was made up by the 791,611 horses (which after deductions are made for cavalry units), which contributed probably the equivalent of 200,000 lorries.52

Ultimately the number of vehicles was not the limiting factor in Soviet transport capacity. As Sokolov has demonstrated, the Soviet Union, despite being an oil-producing nation, imported substantial quantities of high-quality fuel under Lend-Lease. The damage done to the Maikop oil wells in 1942 in advance of the German arrival cut the overall scale of fuel production, and from this point onward, fuel was a scarce commodity in the Soviet war effort.53

Transportation in the Combined-arms army

Rifle division transport

The backbone of the Soviet combined-arms army was the rifle divisions, of which there were 376 in 60 field armies in July 1943. In the reforms that followed the defeats of 1941, the rifle division went through a series of changes that led by December 1942 to a satisfactory establishment that would last almost to the end of the war. This was Shtat 04/550 Rifle Division54 with 9,435 men, 44 artillery pieces, 48 anti-tank (AT) guns, 160 mortars, 605 machine guns, and 212 AT rifles. The division fielded 1,719 horses, 437 wagons, and 268 carts, 125 motor lorries and trucks, 15 tractors, and four passenger cars as transport to move the men, weapons, equipment, and supplies. In the Soviet system, only food and fodder were supplied on a daily basis and were collected by the divisional transport company from army depots. Everything else, from munitions to intendant’s stores to medical and veterinary support, was centrally controlled by General A. V. Khrulev, Chief of the Rear, who directed these supplies and services via front and army rear headquarters to where they were most needed. Rather than struggling to keep every division topped up to a set standard, the front rear headquarters aimed to concentrate supplies with the divisions that were fighting and advancing, and these supplies were delivered to the divisions by army transport, which meant that rifle divisions functioned with only minimal transport.

The basic unit of the 04/550 Division was the rifle company of 143 personnel in three platoons, with two 50 mm mortars and a maxim machine gun and which possessed one horse and a cart. The rifle battalion had 619 personnel with two 45 mm AT guns, nine 82 mm mortars, and nine AT rifles and on paper possessed one bicycle, eight artillery horses, 39 draft horses pulling one telephone cart, one medical cart, 15 one-horse wagons, eight two-horse wagons, two caissons, and three infantry field kitchens. This was less than half the transport of its German counterpart, while a British infantry battalion possessed 27 motorcycles, 12 cars, 28 trucks (15 cwt), 13 lorries (3-tonne), and 38 carriers.

The Rifle Regiment (Shtat 04/55155) had 2,474 personnel in three battalions with signals, SMG, AT rifle companies, mortar, AT gun, and regimental gun batteries for a total of 36 maxims, 54 AT rifles, eighteen 50 mm, twenty-seven 82 mm, and seven 120 mm mortars, 12 45mm at guns, and four 76 mm regimental guns. The transport assigned was 13 bicycles, one GAZ-AA trucks, and seven ZIS-5 lorries (for the 120 mm mortars), 27 riding horses, 89 artillery horses, 233 draft horses, 10 telephone carts, two pharmacy carts, three medical carts, four medical wagons, 47 one-horse wagons, 72 two-horse wagons, 12 caissons, 10 infantry field kitchens (four-wheeled), five cavalry field kitchens (two-wheeled), and two chemical carts type KDP. The principal users of horse-drawn transport were the transport company with 29 two-horse wagons and the regimental gun and mortar batteries.

The other large unit in the division was the Artillery Regiment (Shtat 04/ 55256), which had 927 personnel, 20 field guns, and 12 medium howitzers. The motor transport was limited to four ZIS-5 lorries in the transport section and a single GAZ-Type A workshop with 15 STZ-5 tractors to pull the medium howitzers. In terms of horses, there were 154 riding horses, 414 artillery horses, and 50 draft horses pulling the field guns, and a total of 27 carts, 153 wagons, and eight infantry type field kitchens (four-wheeled).

Of the remaining Divisional units, the bulk of the motor vehicles were concentrated in the Transport Company (Shtat 04/55957) with 45 ZIS-5 and two GAZ-AA lorries; the Medical Battalion (Shtat 04/56158) with 10 GAZ ambulances and three ZIS-5 for rations and two field kitchen trailers; Chemical Defense Company (Shtat 04/55859) with six GAZ-AA chemical trucks; and the AT Gun Battalion (Shtat 04/55460) with one car, five GAZAA (munitions, fuel, and rations) and 12 ZIS-5 to pull the guns.

This meant that the only motorized weapons in the entire division were the 12 AT guns, 12 medium howitzers, and 21 heavy mortars; every other weapon was horse-drawn or carried by soldiers. The corresponding Guards Rifle Division (Shtat 04/500) had a higher complement of personnel at 10,743, with four extra field guns and additional mortars and machine guns, yet retained the same vehicle standard. However, it should be noted that these Soviet units were never at establishment strength, ranging between 5,000–7,000 personnel at the start of offensives and down as low as 3,000, with typically 100 vehicles and 900 horses by the end of offensive operations, with the proportion of horses and infantry typically remaining more or less constant.61 Rifle divisions carried 186 tonnes of munitions (1.5 boyevoy komplekt), 26.1 tonnes food (2 sutodachi), 11.7 tonnes fodder (2.9 tonnes grain and 6.8 tonnes hay), 9.9 tonnes fuel (0.5 zapravki), for a total of 233.7 tonnes, while the motor transport company had a capacity of 129 tonnes,62 with the balance carried by horse-drawn wagons along with the soldiers’ baggage. Typically two-thirds of the division’s load was hauled by horses.63

Combined-arms army combat transport

Combined-arms armies varied widely in size and number of units depending on their operational tasks; however, the 7th Guards Army (7GA) on 3 August 1943 during Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev can serve as a typical example for the second period of the war. The 7GA had defended the line of the Seversky Donets river south of Belgorod during the battle of Kursk from attack by Armee-Abteilung Kempf and by the beginning of August had recovered the lost ground up to the river. The main attack went in on 3 August to the north of Belgorod mounted by the 5th and 6th Guards Armies and 53rd Army with the exploitation mounted by 5th Guards and 1st Tank Armies. 7GA launched a supporting attack cross the river and advanced south-westwards along a 20-mile sector, passing just to the south of Kharkov.64

The 7GA contained eight rifle divisions, six artillery brigades and regiments, four tank brigades and regiments, one SP artillery regiment, two armored trains, and four AA artillery regiments (PVO),65 for a total of 54,757 personnel, 5,885 horses, 1,758 motor vehicles, 420 guns, 250 AT guns, 89 AA guns, and 79 tanks in combat units.66 The rifle divisions ranged in size from 8,308 down to 3,698 personnel, on average 5,023 strong with 717 horses and 105 motor vehicles, and since most were Guards Rifle Divisions (Shtat 04/500), their establishments were 10,670 personnel (5,647 short), 1,867 horses (1,150 short), and 126 vehicles (21 short). There were 858 vehicles and 5,816 horses with the rifle divisions, so horses were still hauling more than half the load in the rifle units, although there were very few horses present in the remainder of the army — that is, with artillery, AT artillery, AA artillery, tank and mechanized forces, AT rifle, or penal units. These had 902 vehicles (of which 300 were with tank units) and only 69 horses, so they took half the motor transport yet only had 253 guns: fifty 152 mm howitzers, eighty-one 76 mm divisional guns, 33 AT guns (probably 45 mm), and 89 AA guns (seventy-seven 37 mm mounts, twelve 85 mm guns with 114 DShK machine guns). Of the 506 guns with the rifle divisions, only seventy-six 122 mm howitzers and 96 AT guns (twelve 45 mm in the AT battalion of each division) were hauled by motor vehicles; the remaining 334 were horse-drawn.

The importance of this information is clear — half the army’s artillery was horse-drawn, while motor vehicles were reserved for the AT guns or howitzers or AA guns, which were too heavy to pull with horses. Also it has to be remembered that a substantial part of any Soviet artillery strike came from mortars, and the four hundred eleven 82 mm mortars were man-portable, where only one hundred forty-four 120 mm mortars were motorized.

A complete breakdown of the motor fleet on 15 May 1943 for the entire army, which covers 124 separate combat and rear units — ranging in size from divisions down to single offices — shows that the establishment was 3,564 vehicles (252 cars, 2,760 lorries, and 552 specials such as buses, workshops, tankers, and ambulances), and the actual number of vehicles present was 2,904 (306 cars, 2,174 lorries, and 424 specials) or 60%. This disguises substantial shortfalls in the establishment for heavier vehicles, which was 1,471, where only 571 ZIS-5, 13 ZIS-6, 15 ZIS-42, eight YAG, and 28 Studebakers were available (the bulk of the latter were in the 8th Anti-Tank Destroyer Brigade). The balance between national, imported, and trophy vehicles by their type is shown in Table 6, which stresses the large proportion of national vehicles at 69%, the minimal impact of Lend Lease at 10% (with even fewer lorries), and the heavy reliance on trophy vehicles at this stage of the war, which made up 20% of the fleet. Only in light passenger cars did imported and trophy vehicles make a significant contribution.

By February 1945, 7GA (2nd Ukrainian Front) was finishing Operation Budapest, with a motor fleet as laid out in Table 7. On 17 February 7GA had 69,279 personnel and 3,349 vehicles in combat units (May 1943: 54,758 personnel and 1,758 combat vehicles), of whom 48,139 were infantry with 1,258 vehicles, and 21,140 were in support units with 2,091 vehicles. Rifle divisions averaged 4,376 men and 114 vehicles, while as before the support units were all motorized.68 The motor fleet now had a higher proportion of imported and trophy vehicles; however, the surprising feature was that the trophy vehicles outnumbered the imported ones by more than 2 to 1, and overall the number of imported 2½-tonne trucks was only 386, and these were largely in artillery or tank units, the dozen or so found in each rifle divisions replacing the earlier tractors.69 The entire army had fewer combat vehicles than a single British infantry division.

Combined-arms army rear transport

It is possible to gain an idea of the transport used by the rear units of the 7GA by comparing the total number of vehicles with 1,758 in combat units for August 1943,70 with the detailed breakdown available for 15 May.71 This shows a total of 2,904 vehicles divided among 1,980 in combat units, 135 signals, 50 administration, 209 sanitary/veterinary, 244 workshops and

depots, 17 miscellaneous, 68 road maintenance and operation, 24 fuel supply platoon, 62 in the 835th Separate Staff Motor Platoon, and 163 in the 185th Separate Motor Transport Battalion. In addition, the rear included three separate horse-drawn transport companies and two with oxen engaged in road maintenance. The 835th Separate Staff Motor Platoon comprised 27

cars, 23 GAZ-AA, while the 185th Transport Battalion had 118 GAZ-AA, 34 ZIS-5, and in both cases the balance was in liaison cars, buses, fuel, and workshop trucks.72 There is little change in this roster of vehicles in the reports of 15 May, 1 June, 20 July, and 22 December.73 However, around the end of June, the 841st Separate Motor Transport Battalion joined from Front reserves, doubling the army’s transport capacity until it left at the start of August. It is probable that both battalions were organized according to Shtat 032/7,74 1 August 1942 with one car, 149 cargo, and eight special lorries, as this is a close match to the personnel shown in the list of rear units of 22 December. Army rear transport in the third period would increase from one or two motor battalions to two or three motor battalions,75 which was quite a

minor increase given the change that took place in the summer of 1943, whereby according to NKO Order №370, 12 July 1943, responsibility for the delivery of supplies from army depots to divisional exchange points was transferred to army transport from divisional transport — which still collected rations/fodder.76

Front transport

During the first period of the war, fronts operated with fairly minimal transport; however, in April 1943 STAVKA transferred a regiment from the reserve fleet to each of eight fronts (Leningrad, North-Western, Western, Central, Voronezh, South-western, Southern, and North Caucasian) to strengthen their transport capabilities (NKO №.0309 27 April 1943),77 and these were powerful units. For instance, the establishment (Shtat 032/75, 22 June 1943) for one type of regiment shows personnel of 1,915 with 16 cars, 958 lorries, and 111 special vehicles. In August, the Steppe front was reinforced by transferring two motor transport battalions and the Voronezh front with five battalions (this clearly relates to the original two battalions with the front).78 The importance of the STAVKA reserve to front transport is shown by the Voronezh front during Operation Rumyantsev, as the front had seven battalions of transport: two came from STAVKA in April and five in August (814 vehicles with capacity of 1860t).79

The 7th Guards Army was part of the Steppe Front (later 2nd Ukrainian Front), which consisted of four combined-arms armies (53rd, 69th, 7th Guards, and 47th) and the 1st Mechanized Corps. To support these units, the front was under strength, with only two motor transport battalions (ОАТь), and so between 27 July and 16 August, STAVKA sent it the 801st, 205th, 5th, 899th and 900th ОАТь with 748 vehicles plus an additional 97 vehicles that returned from the repair shops.80 The front deployed four of these with the armies and kept three as the front reserve. To ensure the supply of fuel, the front only had 98 vehicles with a capacity of 180 tonnes or 0.12 refuellings.

STAVKA reserve

On 13 January 1943, while the Stalingrad Strategic Operation was in full swing, the State Defense Committee (GKO) decided to create a strategic lorry reserve under GKO order № 273981 by taking 65,090 lorries and 2,175 cars from the fronts, military districts, and the navy (out of a total of 293,000 lorries and 22,000 cars or 22% of the total), plus an additional 20,000 vehicles from the civil economy, 40,000 from the next five months’ production, and 30,000 from imports. This gigantic effort clearly fell short, as the November 1942 total of 7,700 vehicles only rose to 37,700 by July 1943 and, as was shown earlier, STAVKA was transferring a substantial number of units back to the fronts in April and August. By January 1944 the total had fallen back to 20,200, and it remained at under 30,000 until the end of the war.

Transportation in operation

7th Guards Army

In the preparatory period of the Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev offensive, the Steppe Front had an establishment of 27,063 vehicles and 2,158 tractors, yet in reality had only 16,406 vehicles (68%) and 1,675 tractors on hand, of which by 3 August, 15,050 were operational in the armies and 487 operational in the front reserve. With each army having 3,000 vehicles plus 1,500 in the 1st Mechanized Corps and several thousand vehicles in the 5th Air Army and front artillery and transport units, this was the extent of the motor fleet. During the course of the offensive, great effort was made to repair vehicles, and numbers rose to 16,656 with a front reserve of 631, while 863 were lost to air attack, artillery fire, and mines.

Fiat truck outside Stalingrad (colourisation by Klimbim)

With front transport largely supporting the Belgorod attack, 7GA mainly had to rely on army and divisional transport. The front regulating station was at Liski with the main railway line running south-west to Valuki where the line turned north to Volokonovka (7GA supply base) following the line of the Oskol River. As the 7GA advanced toward Kharkov, on 12 August its supply base jumped forward 60 km to Volchansk, and the railway line now continued SW past Valuki and turned north at Kupyansk to Volchansk. There were four military roads (VAD) linking Liski with the Oskol River — a distance of 160 km — and 7GA had its army military road running 35 km from Volokonovka to the main cluster of depots and hospitals at Popovka, and then ran 15 km further on toward the front. From the end of the road to the divisional exchange points was a further 25 km, and these were placed 12 km behind the front line. The total distance from the railway to the divisional exchange points (the area of responsibility of army transport) was 75 km, and these distances were retained once the army base moved forward and the front line was outside Kharkov on 23 August.

During the operation (3–23 August 1943) the front transport moved 42,972 tons of cargo (munitions 27,887 tonnes, fuel 7,906 tonnes, other cargo 7,949 tonnes) while the army transport moved 60,000 tonnes. While this sounds impressive (a battalion carried 300 tonnes for 20 days of the operation over 150 km a day), the three front ОАТь could haul this for a maximum of 31 km, while the 10 army ОАТь (two per army plus four STAVKA battalions) could haul 75 km. This suggests that the army roads were fully utilized moving supplies forward from Volokonovka to the front line, while the front road was underutilized and supplies were largely carried forward 160 km by railways from the front depots based around Liski to the army bases on the Oskol River.82

8th Guards Army

As another example of Soviet transport in use, the Vistula-Oder Strategic Operation was launched out of two small bridgeheads over the Vistula, and the original plan envisaged an advance to capture Lodz 180 km away, with Poznan 390 km away as a secondary objective. In the event, the breakthrough happened quickly, the two tank armies drove off into the operational depths undamaged, the German 2 Armee collapsed under the weight of the offensive, while the Panzer counter attack was fended off relatively easily. This left 8th Guards Army in a good state to advance on Poznan, which was reached on 24 January after an advance of just 10 days.83 With three ОАТь to support it, this was about the limit of its advance, especially in the snowy weather of January. Yet the 1st Belorussian Front was aided by several events that altered the course of the offensive. The rapid collapse of the German 2 Armee left most of the standard-gauge railway network intact, and more importantly, sufficient rolling stock was captured to allow trains to be run between the bridgehead at Magnushev and Poznan. Although supplies had to be transshipped over the Vistula between the railhead at Deblin and the bridgehead, sufficient fuel was brought forward to keep both the tank and combinedarms armies advancing. In addition, the railway bridge over the Vistula opened after just eight days, 12 days early, because the railway troops constructed a new 515 m bridge alongside the damaged steel one.84 Even so, the successful advance depended on the capturing of large stocks of food from German depots, especially around Poznan, which allowed the limited motor transport to concentrate on delivering fuel and munitions.

Tempo of operations

German vehicles destroyed during Operation Bagration June 1944 - note Soviet horse and wagon in foreground

A central tenet of this article is that there was little growth in overall transport capabilities for the Soviet field army during the war. While it may have grown in size and in number of vehicles, in both front and armies this extra transport was absorbed by extra artillery, and modest additions to the supply transport would have been needed to meet the increased demand created by the extra guns. This begs the question: In this case, how did the Red Army increase its tempo of operations in the second and third periods of the war? This difference is seen in Operations Bagration and Vistula-Oder, with tank armies moving 30 km a day and combined arms armies 15 km a day in 1944 and then tank armies moving up to 70 km a day and combined-arms armies 30 km a day in 1945. This is especially relevant to the rifle divisions, which saw little improvement in their motor transport numbers; nor can extra mobility be ascribed to improved technology, as these units received few Lend-Lease vehicles. It has to be remembered that half the transport of these divisions was horse-drawn, and the increasing number of horses was a significant factor in the mobility of units at regimental level and below. It is here that the answer lies, as truly mobile horse-drawn armies such Kankrin’s Imperial Russian army or Sherman’s army at the end of the Civil War were perfectly capable of traveling long distances at similar speeds of 30 km a day, once they got the balance right between their transport capacity, their daily demand, and their combat power, drawing food and fodder from the agricultural area through which they marched, using their wagons as a reserve supply, and where a vital element was keeping the weight of equipment and baggage within limits. These were all characteristics of the late war Red Army, and when taken with the increased capacity of the Management of Military Restoration Work (UVVR) and railway troops to restore damaged railway lines behind the advancing troops, it offers an explanation of the increased tempo of combined-arms armies in 1944–45. Another factor to consider was that the design philosophy of ‘deep battle’, as applied in the late war period, that took account of the differences in mobility between the fully motorized tank armies and the partly horse-drawn/ motorized combined arms armies by assigning them different though interrelated roles in the overall operation.

Conclusion

The Red Army during the Soviet-German War managed to improve both the quantity of combat power it could muster for an attack, the tempo of its operations, and the depth and speed of sustainable advance into enemy territory. That this was a difficult balance to achieve is illustrated by the fact that around half of all Soviet offensives failed at some point.85 Similarly, the German offensives of 1941 and 1942 failed to achieve this balance because their advances were not sustainable due to a lack of logistical support. The correct balance of mobility and combat power did not arise from mechanization but from an understanding of the interaction of the three tyrannies of weight, demand, and distance.86 This balance has always been elusive for armies, ever since railways and steamships provided them with the means to deliver and supply mass armies to a rail head or port. The challenge was always to move a distance away from a rail head or port and the mass transport it represented. Despite the pre-war Soviet economy concentrating on producing lorries and tractors, it was still too small to provide sufficient production to equip the Red Army with anything like enough transportation to meet its requirements from motor vehicles alone. The huge losses in vehicles during the first year of the war meant that the Red Army only survived by stripping the civilian economy to the bone. So while Lend-Lease was important, it barely provided sufficient numbers to restore the fleet to pre-war levels, and the transportation of the field army was at its lowest ebb in the summer of 1943. To face this crisis, the new vehicles were given to the most important units — tank armies and breakthrough artillery units. From a transport perspective, the field army in the later war years did not improve its level of motorization — rifle divisions remained largely horse-drawn, and additional vehicles were used to pull a greater quantity of supporting artillery. Soviet forces gained their mobility by a combination of light weight, low demand, and living off the land, following principles very similar to those proposed by Kankrin 150 years earlier. Despite this shortage of transportation, the Soviets created a tactical/operational system that successfully managed to combine railways with horse-drawn transport and motor transport in such a way that they could launch and sustain offensives over distances of up to 600 km. This capability ultimately depended on the speed at which the railways could be restored, while more successful breakthroughs and higher rates of exploitation created a virtuous circle where less damage was done by the Germans to the railways, which in turn allowed higher rates of restoration.

Endnotes

1 D. Edgerton, The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2011, p. 33.

2 W. J. White, Economic History of Tractors in the United States, Research Triangle Institute, Economic History Association, 2006, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/economic-history-of-tractors-in-the-united-states/.

3 F. M. L Thompson and British Agricultural History Society, Horses in European Economic History: A Preliminary Canter, The British Agricultural History Society, Reading, 1983, p. 108.

4 T. C. Barker, ‘The Delayed Decline of the Horse in the Twentieth Century’, Horses in European Economic History — A Preliminary Canter, British Agricultural History Society, 1983, p. 110.

5 A. Maddison, ‘Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1–2008 AD’, Economic Performance through History, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/oriindex.htm (accessed 17 June 2017).

6 Статистическое издательство ЦСУ СССР, ‘Статистический справочник СССР за 1928 г.’ [Statistical Directory of the USSR for 1928], Проект «Исторические Материалы», 1928, http://istmat.info/node/20228 section VI part 2 (accessed 16 August 2018).

7 S. Melnikova-Raich, ‘The Soviet Problem with Two “Unknowns”: How an American Architect and a Soviet Negotiator Jump-Started the Industrialization of Russia, Part I: Albert Kahn’, IA: The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology, 36 (2010), p. 59.

8 ‘Статистические Динамические Ряды За 1913–1951 Годы’ [Statistical Dynamic Series for 1913–1951 Years], Проект«Исторические Материалы», http://istmat.info/node/40054 section II, p. 102 (accessed 1 November 2017).

9 P. Howlett, Great Britain, and Central Statistical Office, Fighting with Figures, H.M.S.O., London, 1995, p. 176Table 7.30.

10 J. Kothe, ‘Statistisches Jahrbuch Für Das Deutsche Reich 1939’, DigiZeitschriften: Inhaltsverzeichnis, https://www.digizeitschriften.de/dms/toc/?PID=PPN514401303_1937, p. 183 (accessed 1 October 2017).

11 N. Jasny, The Socialized Agriculture of the USSR: Plans and Performance, Stanford University Press, 1949, p. 324 Table 25 and p. 458 Table 40.

12 ЦУНХУ, ‘Картотека Автомобильного Транспорта. Данные По Отраслям Народного Хозяйства и Наркоматам. 17 Августа 1945 г.’ [Card File of Motor Transport. Data on the Branches of the National Economy and the People’s Commissariats. August 17, 1945], RGAJe f.1562, Op.329, d.1846, l.74–135, Проект «Исторические Материалы»,http://istmat.info/node/45251 p. 4 (accessed 7 October 2017).

13 H. Boog et al., Germany and the Second World War: Volume 4: The Attack on the Soviet Union: The Attack on the Soviet Union, ed. E. Osers, trans. D. S. McMurry and L. Wilmott, Har/Map edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1998, p. 931.

14 GAVTU, ‘Отчет Управления Снабжения ГАВТУ КА о Работе За Период Великой Отечественной Войны’ [Report of the Headquarters of the GAVTU Staff on the Work during the Great Patriotic War] ЦАМО. Ф. 38. Оп. 11584. Д. 396. Л. 9–89’, in Главное Автобронетанковое Управление: Люди, События, Факты в Документах [The Main Auto-Armoured Directorate — People, Events, Facts in Documents], vol. 4, 2007, p. 668 item 530.

15 R. Huhn Jones, Roads to Russia: United States Lend-Lease to the Soviet Union, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1980, Appendix A, Table IV.

16 ‘RUSSIA (BRITISH EMPIRE WAR ASSISTANCE)’, Hansard, 16 April 1946,’ https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/ commons/1946/apr/16/russia-british-empire-war-assistance (accessed 14 May 2018).

17 Chief of Military History, ‘The United States Army in World War II: Statistics — Lend Lease’, Office of the Chief of Military History Department of the Army, 15 December 1952, pp. 25–27 Table LL–14; Report to Congress on LendLease Operations, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950.

18 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, ‘077 German Motor Vehicles Industry Report’, Munitions Division, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, January 1947, Appendix Tables 109 and 110.

19 M. van Creveld, Supplying War: Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge , 2004, p. 234.

20 War Office, ‘Field Service Pocket Book Pamphlet No 6 Mechanized Movement by Road 1941’, December 1941, pp. 29–32.

21 ‘H.Dv.g. 90 Versorgung des Feldheeres (V.d.F.) Teil II (geheime),’ 1941, 424029928 (SWB catalog no.), Württembergische Landesbibliothek, p. 18.

22 F. Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism: 15th–18th Century, Collins, London, 1985, Vol. 1, p. 429.

23 ‘TM-9–801 Truck GMC 6 × 6 CCKW-352 & 353 and GMC 6 × 4 CCW-353 — Operators Manual’, U.S. Army, 1944, United States Combined Arms Centre Library, http://usacac.army.mil/cac2/cgsc/carl/wwIItms/TM9_801_1944.pdf, pp. 19 and 35.

24 ‘U.S. Truck Loading Reference Data’, Headquarters Office of the Chief of Transportation, March, 1944, U.S. Army Combined Arms Center Library, pp. 73–74.

25 GAVTU, ‘Отчет Управления Снабжения ГАВТУ КА о Работе За Период Великой Отечественной Войны’ [Report of the Headquarters of the GAVTU Staff on the Work during the Great Patriotic War], ЦАМО. Ф. 38. Оп. 11584. Д. 396. Л. 9–89, p. 691.

26 Dr. L. Niehorster, ‘Infanterie-Division (1. Welle), German Army Organizations, 1.09.1939’, World War II Armed Forces — Orders of Battle and Organizations, http://www.niehorster.org/011_germany/39_organ_army/39_id-1_ welle.html (accessed 4 November 2017).

27 F. Halder, The Halder Diaries: The Private War Journals of Colonel General Franz Halder, Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 1976, Vol. III, p. 55.

28 B. R. Kroener, R.-D. Muller, and H. Umbreit, Germany and the Second World War: Vol. 5 Part 1: Organization and Mobilization of the German Sphere of Power. Part I: Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources, 1939–1941, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000, p. 739.

29 W. Keilig, Das Deutsche Heer, 1939–1945: Gliederung, Einsatz, Stellenbesetzung [The German Army, 1939–1945: Organization, Deployment, Recruitment], Podzun, Bad Naubeim, 1956, Band 3 folio 100, pp. 2–3. Gesamtzahl der Divisionen des Feldheeres 1939–1942.

30 ‘H.Dv.g. 90 Versorgung des Feldheeres (V.d.F.) Teil II (geheime)’, pp. 20–21.

31 D. Gerhold, Road Transport in the Horse-Drawn Era, Scholar, Aldershot, 1996, pp. 30–31 and 55.

32 G. Perjés, ‘Army Provisioning, Logistics and Strategy in the Second Half of the 17th Century’, Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 16 (1970), p. 15.

33 R. Kane, A System of Camp-Discipline, Military Honours, Garrison-Duty, and Other Regulations for the Land Forces, Collected by a Gentleman of the Army. In Which Are Included, Kane’s Discipline for a Battalion in Action. To Which Is Added, General Kane’s Campaigns of King William and the Duke of Marlborough, 1757, Table XIII.

34 E. F. Kankrin, Über Die Militairökonomie Im Frieden Und Krieg Und Ihr Wechselverhältniss Zu Den Operationen — Drei Band, 3 vols., St Petersburg, 1820, http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/ bsb10526340_00005.html, Band 2 p. 8 (accessed 16 August 2018).

35 E. Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1988, pp. 284–289.

36 M. van Creveld, 2004, op. cit., pp. 110–111.

37 R. L. DiNardo, Mechanized Juggernaut Or Military Anachronism?: Horses and the German Army of World War II, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2008, p. 47.

38 L. H Addington, The Blitzkrieg Era and the German General Staff, 1865–1941, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 1971, p. 93.

39 H.G.W. Davie, ‘The Influence of Railways on Military Operations in the Russo-German War 1941–1945’, Journal of Slavic Military Studies 30 (2017), pp. 321–346, doi:10.1080/13518046.2017.1308120, p. 336.

40 D. M. Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed: The Battles for Smolensk, July–August 1941 Volume 1: The German Advance, The Encirclement Battle, and the First and Second Soviet Counteroffensives, 10 July–24 August 1941, Helion & Company, Solihull, 2010, Chapter 4.

41 N. Davies, White Eagle, Red Star: The Polish-Soviet War 1919–20, Pimlico, London, 2003, p. 196.

42 Управление изучения опыта войныГенерального Штаба Вооруженных Сил Союза ССР, ‘6. МатериальноТехническое Обеспечение Висла-Одерскоя Операции’ [6. Material-Technical Supply during the Oder-Vistula Operation], in Сборник Материалов По Изучению Опыта Войны [Collection of Materials for the Study of the Experience of War], vol. 25, 1947, p. 60; И. М. Ананьев, Танковые армии в наступлении. По опыну великой отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг. [Tank Army on the Offensive: According to the Experience of the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945], Воннпое Издательство, Москва, 1988, p. 412 Table 10.

43 GAVTU, Отчет Управления Снабжения ГАВТУ КА о Работе За Период Великой Отечественной Войны [Report of the Headquarters of the GAVTU Staff on the Work during the Great Patriotic War], ЦАМО. Ф. 38. Оп. 11584. Д. 396. Л. 9–89.

44 ЦУНХУ, Картотека Автомобильного Транспорта. Данные По Отраслям Народного Хозяйства и Наркоматам. 17 Августа 1945 г. [Card File of Motor Transport. Data on the Branches of the National Economy and the People’s Commissariats, 17 August 1945] RGAJe f.1562, Op.329, d.1846, l.74–135.

45 Other discrepancies include the table on p. 676 of the GAVTU report in section I.6.A Losses of the Red Army, which does not add up and has to be reconstructed from other tables; likewise domestic production given to the Ministry of Defense (NKO) is given as 150,400 in the table on page 680 and as 162,600 in two tables on page 673. Similarly there is a 4,100 vehicle production discrepancy for 1941 when the combination of the 73,200 pre-war production in the table on p.679 and 46,100 wartime one on p.680 — a total of 119,300 — is compared against a source such as Harrison’s Accounting for War, which shows a total of 124,176. There are material balances given to calculate losses on p. 676 for the Red Army and p. 677 for the civil economy; however, they use different figures for transfers from the Army to the civilians, 30,300 for the first table and 72,500 for the second. There are issues of timing, as the first table on p. 680 shows national production for 1943 of 47,900 (which is close to those given in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia of 49,266), yet the first table on p. 673 shows the army receiving 53,900 new vehicles in 1943, a figure confirmed by the average monthly receipts. Similarly, there are discrepancies surrounding the allocation of vehicles: On p. 673 the number of imported vehicles received by the army is 282,100, while on p. 690 the total number imported is 312,600, leaving a balance of 30,500. Part of this discrepancy went to the civil economy; the figures would suggest 25,500, but there is a balance of 5,000 vehicles, which probably went to other Directorates such as GAU KA and do not appear in the GAVTU KA figures. See M. Harrison, Accounting for War: Soviet Production, Employment, and the Defence Burden, 1940–1945, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002, Table C.1, and ‘Automobile Production Statistics’, in The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, (n.d.) (1970–1979), 3rd ed., The Gale Group, Inc. A data appendix showing the principal tables used in this article can be found at https://www.hgwdavie.com/data-appendix/.

46 ЦУНХУ, Картотека Автомобильного Транспорта. Данные По Отраслям Народного Хозяйства и Наркоматам. 17 Августа 1945 г. [Card File of Motor Transport. Data on the Branches of the National Economy and the People’s Commissariats, 17 August 1945] RGAJe f.1562, Op.329, d.1846, l.74–135.

47 Ibid.

48 Н. Андронников, В. Гнездилов, and В. Фесенко, Великая Отечественная Война 1941–1945. Действующая Армия [The Great Patriotic War — The Operational Army], Военная История Государства Российского в 30 Томах, Кучково поле, Moscow, 2005, p. 534 Appendix 3.

49 А.Э. Сердюков and В.А. Золотарев (ред.), Великая Отечественная Война 1941–1945 Годов : В Двенадцати Томах [The Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 in 12 Volumes], Военное Изд-во, 2011, Moscow, TOM.1 p. 8. In the Soviet historiography the war is divided into three periods, the first from 22 June 1941 to November 1942, the second from November 1942 to December 1943, and the third from January 1944 to 9 May 1945.

50 Полковник В. ГУРКИН, ‘Ликвидация окруженной группировки (операция „Кольцо“ в цифрах)’ [Elimination of Encircled Forces — Operation ‘Ring’ in s], Военно-исторический журнал [Military History Journal] Issue 2 (1973), pp. 34–42.

51 И. М. Ананьев, Tankovye armii v nastuplenii, p. 87 and 235; ‘Сведения о Наличии Автотранспорта 2 Гв. ТА На 1.12.44 г.’ [Information about the Presence of Vehicles in 2 Guard Tank Army on 1.12.44.], 4 December 1944, f.307 op.4148 d.263 l.576, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/documents/view/?id=134493870 (accessed 16 August 2018).

52 Allowing 350 kg draft weight per horse and 200,000 horses for cavalry and average load of Soviet lorry at 2 tonnes.

53 B. V. Sokolov, ‘The Role of Lend-Lease in Soviet Military Efforts, 1941–1945’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 7 (1994), p. 571. doi:10.1080/13518049408430160.

54 ‘Штат № 04/550 Управления стрелковой дивизии (военного времени)’ [Establishment No 04/550 Headquarters Rifle Division (Operational Army)], Память народа::Поиск документов частей, f.214 op.1437 d.519, Arkhiv TsAMO, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/documents/view/?id=262168425 (accessed 11 October 2017).

55 ‘Штат № 04/551 Стрелкового полка стрелковой дивизии (военного времени)’ [Establishment No 04/551 Rifle Regiment Rifle Division (Operational Army)], Память народа::Поиск документов частей, f.214 op.1437 d.519, Arkhiv TsAMO, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/documents/view/?id=262168438 (accessed 11 October 2017).

56 ‘Штат № 04/552 Артиллерийского полка стрелковой дивизии (военного времени)’ [Establishment No 04/552 Artillery Regiment Rifle Division (Operational Army)], Память народа::Поиск документов частей, f.214 op.1437 d.519, Arkhiv TsAMO, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/documents/view/?id=262168469 (accessed 11 October 2017).

57 ‘Штат № 04/559 отдельной автороты подвоза стрелковой дивизии (военного времени)’ [Establishment No 04/559 Separate Motor Transport Company Rifle Division (Operational Army)], Память народа::Поиск документов частей, f.214 op.1437 d.519, Arkhiv TsAMO, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/documents/view/?id= 262168521 (accessed 11 October 2017).

58 ‘Штат № 04/561 отдельного медико-санитарного батальона стрелковой дивизии (военного времени)’ [Establishment No 04/561 Separate Medical Sanitary Battalion Rifle Division (Operational Army)] Память народа::Поиск документов частей, f.214 op.1437 d.519, Arkhiv TsAMO, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/documents/ view/?id=262168533 (accessed 11 October 2017).

59 ‘Штат № 04/558 отдельной роты химической защиты стрелковой дивизии (военного времени)’ [Establishment No 04/558 Separate Company Chemical Defence Rifle Division (Operational Army)], Память народа::Поиск документов частей, f.214 op.1437 d.519, Arkhiv TsAMO, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/documents/ view/?id=262168515 (accessed 11 October 2017).

60 ‘Штат № 04/554 Отдельного истребительно-противотанкового дивизиона стрелковой дивизии (военного времени)’ [Establishment No 04/554 Separate AT Division of Rifle Division (Operational Army)], Память народа:: Поиск документов частей, f.214 op.1437 d.519, Arkhiv TsAMO, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/documents/view/?id= 262168489 (accessed 11 October 2017).

61 D. M. Glantz, Colossus Reborn: The Red Army at War : 1941–1943, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2005, pp. 89ff.

62 Полковник И. Малюгин, ‘Развитие и совершенствование тыла стрелковой дивизии в годы войны’ [Development and Improvement of the Rear of the Rifle Division during the War Years], Военно-исторический журнал (VIZh) [Military History Journal] 11 (1978), p. 92.

63 Col. Malyugin claims that supplies were only moved by the Motor Company in two lifts. Yet he forgets that each Artillery Battalion had a Munition Platoon of 24 wagons, and the Artillery Regt as a whole had 153 wagons and 34 carts.

64 ‘Схема Устройства Тыла и Базирование 7’ Гв. А [Scheme of the Rear Units and Bases of the 7th Guards Army], Pamyat Naroda, 13 August 1943, f.341 op.5312 d.280 l.6, Архив ЦАМО, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/documents/ view/?id=133390871 (accessed 16 August 2018).