"I recommend this work for every professional army officer, but particularly those in the operational field who are used to moving units with the stroke of a grease pencil." Major Michael D. Krause, Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

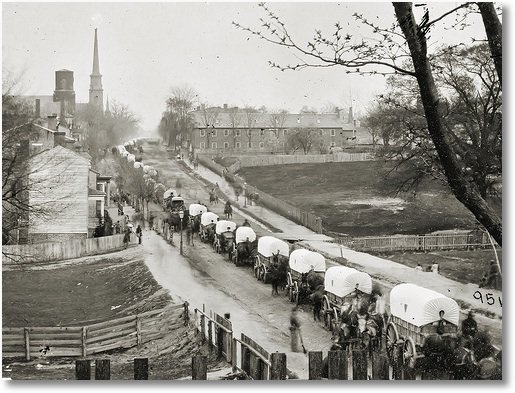

Supply train during the American Civil War

This classic history book was first published in 1977, with a second extended edition in 2004 which added a new retrospective chapter. The inspiration for the book came from Larry H. Addington's The Blitzkreig Era and the German General Staff 1865-1941 and conversations with David Chandler and Christopher Duffy at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. The book has a number of flaws (which Van Creveld mentions in the 2nd edition,) principally that it does not cover the American Civil War, the largest and longest conflict between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Great War and it does not cover naval or amphibious warfare, confining itself to land conflicts. A central theme of the book is that, contrary to historical orthodoxy, armies lived off the land from the resources of the local area through which they marched for most of the period from the Thirty Years War right up to the Great War and despite the advent of metalled roads and railways.

It has had one major critic in John A. Lynn Feeding Mars - Logistics in Western warfare from the Middle Ages to the present who challenged Van Creveld on his term "living off the land" and gave a more detailed and nuanced range of activities such as quartering & billeting, requisitioning, contributions, use of contractors or local markets, rapine & plunder or the étapes (posts along a military road).

He reserves his harshest critique for the section "Some problems with numbers" where he claims that armies must draw their supplies of bread from magazines because there are not sufficient number of ovens in the local area to support the demand for bread from village ovens. His source is G Perjes Army Provisioning, Logistics and Strategy in the Second Half of the 17th Century who in turn uses for primary sources Kankrin (see my earlier posts) for levels of support from local areas and for operational matters M. le maréchal de Puységur's Art de la guerre par principes et par règles. Perjes like Van Creveld came to the conclusion that a theatre of war theoretically had sufficient stocks to support an army of 90,000 men and camp followers, the main problem being the collection of those stocks into the army's area of operations and its processing by milling and baking into finished food products such as bread and sausages. The shortages of local ovens was complemented by the use of army field ovens which were set up in the rear of the army. The transport from ovens to army was only a march to two at most and it does not automatically follow, that the flour had to come from some distant magazine, maybe up to 10 marches away. There is a case to be made for local requisitioning particularly from local towns, acting as agricultural markets. Kankrin is quite clear that an army of this size would exceed the capacity of its local area but as was seen in the Kankrin/Clausewitz model the Low Countries with a population density of 50 inhabitants per km sq (Perjes own figure for 1700) was capable of providing that support from the wider province. As evidence of this we can use Lee Kennett's 1967 classic The French Army in the Seven Year War where he discusses the use of munitionnaires and says "Apparently these organisations relied primarily on France as a source of supply, though every effort was made to obtain these commodities in Germany. The resources of the French border provinces were most used to minimise the costs of transportation." Van Creveld overstates the case for local requisitioning but Perjes and Lynn understate the effort required to move flour to the army. In reality a more complex nuanced picture emerges of the army using the least effort to obtain its supplies where it could.

Sutlers cart and donkey

In the notes Lynn makes a calculation for the consumption of horses of 25 kg (rounded to 50 lb) a day green fodder which then uses through his discourse. Yet Perjes is quite clear that this figure only relates to the 6-8 weeks of campaigning prior to harvest in mid July and that the four months after the harvest the horses were fed dry fodder at a rate of 10 kg a day, all of which "fodder supply was substantially based on requisitions made on the spot.". But ignoring these details, he later claims that "fodder made up 90% of the supply demand so compared to the US Army in WW2, the percentage of fuel needed actually fell!" This is exactly the same kind of misleading figures that he ascribes to Van Creveld. Of course there is a substantial difference to bulk supplies collected from the area immediately surrounding the army camp and those hauled by wagon from some distance away. Lets correct Lynn's figures for the post harvest campaign season: the soldiers and camp followers demand 225,000 lb of food a day, the 40,000 horses demand 800,000 lb a day or 78% of the total demand. However if we are looking at an army supported by a magazine then the EFFORT required looks approximately like this: 225,000 lb hauled 50 miles from a magazine = 11 million lb miles while the horse fodder collected locally at 800,000 lb hauled 5 miles = 4 million lb miles. The horses require 25% of the effort to meet the supply demand while the food requires 75%. Of course food collected from a local town would alter the percentage back against the horses but reduce the amount of total effort required to 5 million lb miles. Additionally he draws attention to Van Creveld's statement that "Whereas even as late as 1870, ammunition had formed less than 1 per cent of all supplies..... in the first twelve months of WW1, the proportion of ammunition to other supplies was reversed, and by the end of WWII subsistence accounted for only 8 to 12 per cent of all supplies." A statement which he calls misleading because there is no explanation that a) the overall supply demand grew b) that other items such as fuel and construction materials were added to the total as warfare became more complex.

Lynn quite rightly states that there might be additional reasons for armies to choose particular methods of supply or other methods, concerns such as discipline, changing motivation of soldiers, military administration but the item he omits which Perjes highlights as being important is seasonality. Armies had to fit in with the changes seasons of the year and the resultant agricultural patterns. Perjes identifies four seasons, winter November to February, "grassing" March to mid May when the horses are fattened up for the forthcoming campaign, the army assembled in cantonments before the start of operations in mid May, pre-harvest operations from mid May to mid July (6-8 weeks) and post-harvest operations from mid July to mid November when the army will go into winter quarters. Campaigning lasts for 27 weeks, though this could be extended into winter, for instance Napoleon's Eylau campaign, with each of these period requiring a different approach to supply. In the pre-harvest period, stores were at a low level after the long winter, so magazines became more important while post-harvest was a time of plenty for local collection.

Another consideration is that the transportation of food supplies by armies, from magazines, over long distances and roads was highly extraordinary. In normal civilian life, road traffic was restricted to high value, lighter, finished products such as textiles, wine, cheese and manufactured goods, while bulk raw materials such as grain or coal were only ever transported within the local area or by river and coastal shipping. Dorian Gerhold has written extensively in this area including Road transport in the horse-drawn era and even when roads had improved in the late 18th century, transport of bulk agricultural products was almost non existant.

Supplying War remains a classic book for all its faults, if only for moving the debate onto new ground and opening up new avenues of research. What was the role of sutlers in supply as a conduit between local markets and the marching army, a task largely carried out by women?

A rather battered copy and heavily annotated of the 1st edition, the 2nd edition is kept quite pristine.